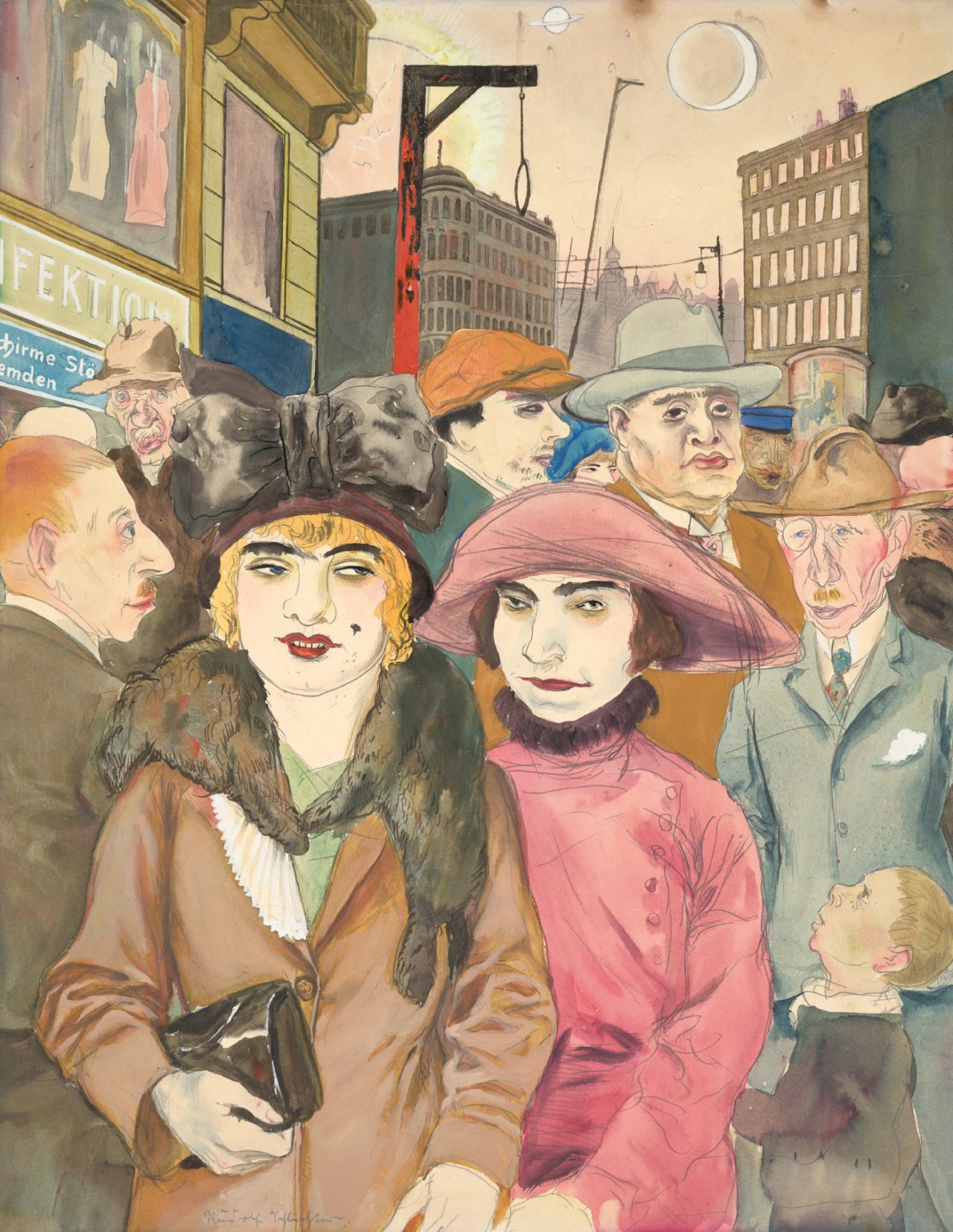

Two women with fashionable silhouettes, short bobbed hair, and a self-confident air push themselves to the fore. Having recently received the right to vote, they are trying out their new role as “New Women” in the daily bustle of Hausvogteiplatz Square, the center of Berlin’s tailoring and fashion scene a hundred years ago. But they attract nary a glance from the male passers-by. The fashion-conscious flair of this and other images by Rudolf Schlichter was noted by the contemporary cultural critic Theodor Däubler: "The costume is what matters; the person underneath, even in times like these, is secondary. We are all wearers of clothes now. The overlordship of those in uniform is only just being abolished.1

Schlichter painted an iconic portrait of Bertolt Brecht with leather jacket and cigar – today in the Städtische Galerie at the Lenbachhaus in Munich – in the same year he created our watercolour. A left-leaning intellectual, he not only shared the famous playwright’s political ideas but also cribbed from his sense for the theatrical. In his painting of Hausvogteiplatz, Schlichter turns the square into a stage where the conditions of the 1920s are allegorically condensed at close quarters: The young and free rub shoulders with lost souls, veterans of the Great War, dandies, and profiteers of the crises already looming on the horizon. Until the late 19th century, Hausvogteiplatz was popularly known as Schinkenplatz (Ham Hock Square), being frequented by both meat sellers and “women of ill repute.” It was also crowded with workshops where ready-to-wear couture was sewn. As these establishments slowly disappeared over the course of the industrial revolution, the square became a hub for alternative business models: elegantly dressed women whose tailoring shops had fallen on hard times because their customers no longer bought from them turned to prostitution.

By way of emphasizing the hopelessness of the scene, the artist places a gallows, colored a garish red, before the striking architectural backdrop, as a cautionary reminder of the violently suppressed Communist uprising in Berlin of 1918-19 and thus a prophesy of future social cataclysm. Beyond his outspoken advocacy of left-wing causes, Schlichter is also known as a pioneer of the New Objectivity style alongside George Grosz and Otto Dix, and as an illustrator for the Malik publishing house. In this image, he elevates an evening street scene with biting satire and socio-critical verismo to a visual showcase of modern history, one full of misery and yet also throbbing with decadence.

1 Quoted from the Exhibition Catalogue: Rudolf Schlichter, Tübingen/Wuppertal/Munich 1997/1998, p. 22