Exhibition

Margaret Kilgallen. New York, The Drawing Center, 1997

During her brief yet remarkably productive career of just over ten years, the American artist Margaret Kilgallen created a multifaceted body of work inspired by folk art, feminism, and her life on the West Coast—a body of work that has only recently begun to receive the recognition it deserves.

Born in 1967 in Washington, D.C., Kilgallen found her way to San Francisco through her studies in Colorado, where she met the artist Barry McGee. Together, they lived in the Mission District, which during this period was a lively neighborhood full of immigrants and artists. Their bohemian life was simple: furniture picked up from the street, clothing from thrift stores—and her artistic practice was deeply influenced by this lifestyle. She worked on found materials and discarded objects, such as cardboard, plywood, signs, and old book pages.

Her visual language drew inspiration from the hand-painted signs in her neighborhood, American and Indian folk art, and Latin American art. Alongside McGee, she soon became one of the defining figures of the San Francisco street art scene. For her, graffiti and murals were the most honest form of art—visible to everyone and free from hierarchies. Under the pseudonym ‘Matokie Slaughter’ named after a 1940s banjo player, Kilgallen left her mark on the city—and even on freight trains, in the true spirit of the ‘hobo lifestyle‘.

At the same time, Kilgallen worked as a bookbinder at the San Francisco Public Library. Craftsmanship lay at the heart of her practice: “I like things that are handmade, and I like to see people’s hands in the world.” She loved the imperfect, the human. Inspired by the typography of old books, she limited her color palette mainly to black and red. Her experiments with printing techniques, lettering, and sign painting led to the distinctive two-dimensionality of her works.

Books and letters held deep meaning for her—as vessels of knowledge, intimacy, and language. Already during the late 1990s, she lamented the loss of handwritten words in the age of the Internet. She chose words based not on meaning, but instead on sound and form.

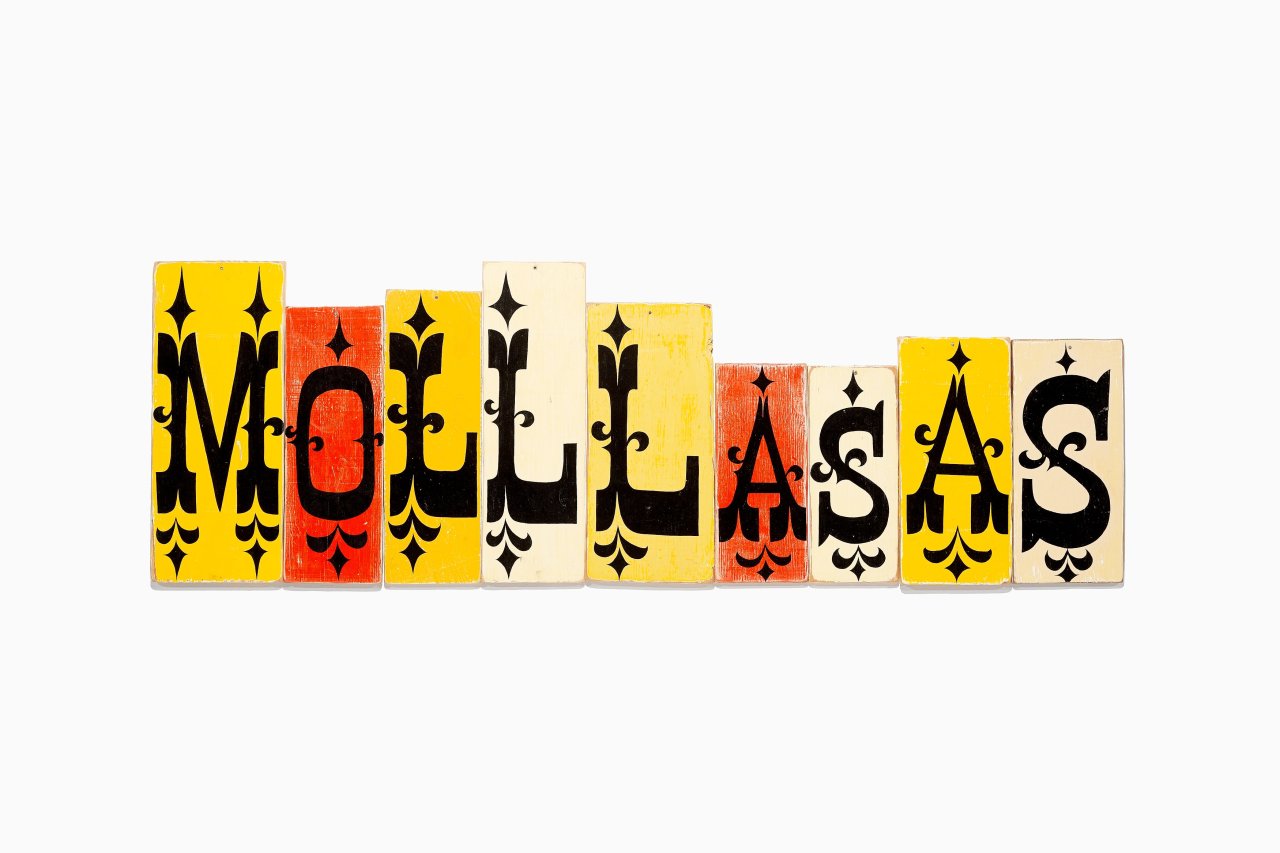

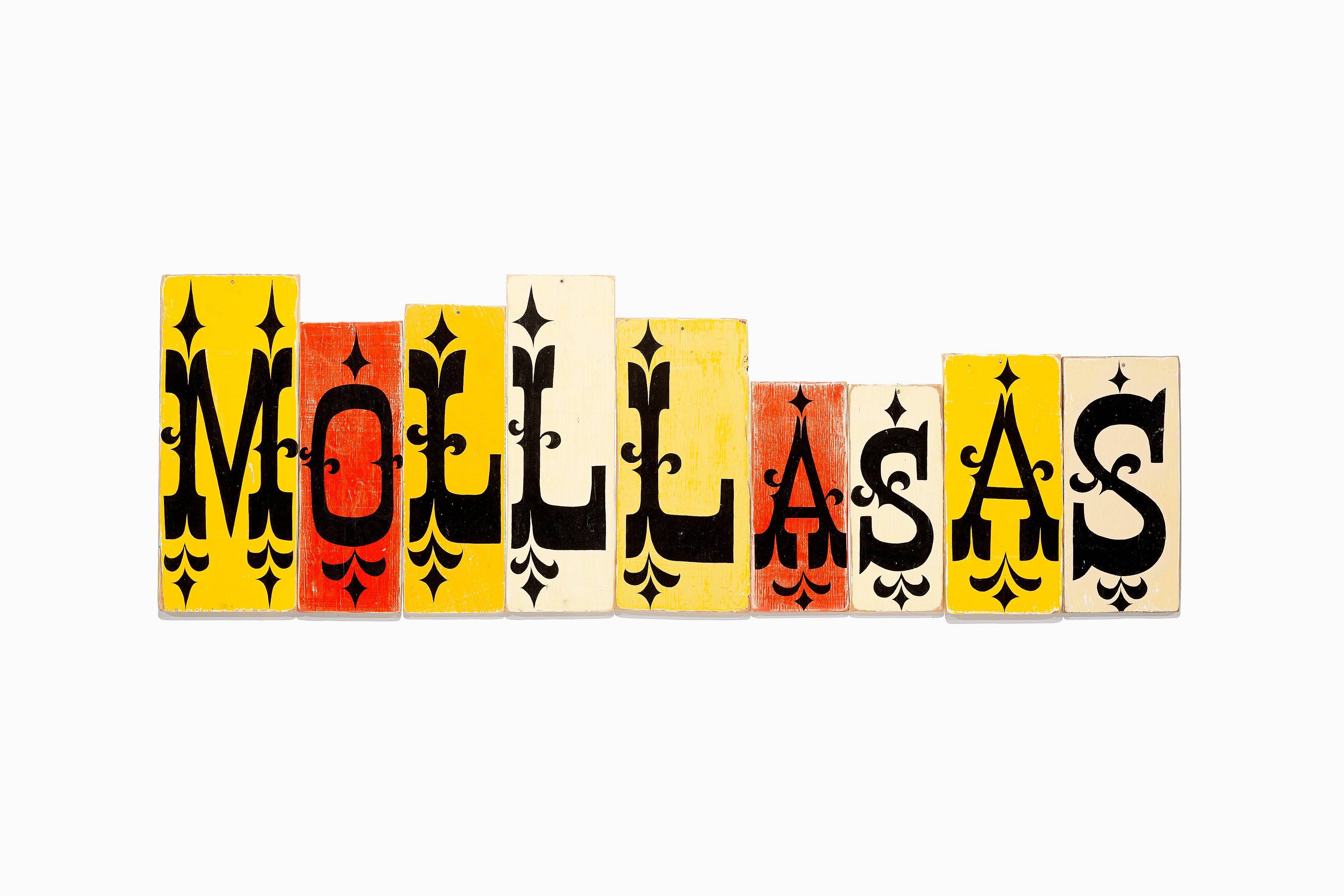

Our work is particularly characteristic: the letters are stylized and executed in archaic capital letters. ‘Molllasas’ is derived from molasses. By deliberately distorting the word, Kilgallen emphasized sound, rhythm, and structure, rendering the actual meaning of the word a secondary concern. The winding, rhythmic letters stand in striking contrast to the imagery of a viscous, sugary mass. There is a kind of circular logic to this: molasses, too, is a form of product-waste—similarly to the materials upon which the work was created—yet both have gained a new purpose.

Kilgallen admired strong, unconventional women such as Fanny Durack, the first female Olympic swimming champion, or Matokie Slaughter, her namesake alter-ego—and she herself remained steadfast until the end. During her pregnancy, a cancer she had overcome in earlier years returned. Devoted entirely to both her art and to her unborn child, she worked tirelessly on her contribution to the group exhibition ‘East Meets West’ at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia. However, her health deteriorated rapidly, and Kilgallen passed away on June 26, 2001—three weeks after the birth of her daughter, Asha. Her sudden death marked the end of a promising artistic career that was just beginning to flourish.

In recent years, her work has finally received the long-overdue institutional recognition it deserves, with her largest solo museum exhibition to date, ‘that’s where the beauty is.’, shown between 2020 and 2021 at the Aspen Art Museum, moCa Cleveland, and the Bonnefantenmuseum Maastricht.

Felicitas von Woedtke

Subject to change - Please refer to our conditions of sale.